What the heck are SENTENCES and PERIODS?

Maybe you've heard about these two terms, may not. Regardless, you have for sure listened and/or played them many many times. Let's dive in to understand what they are!

May 20, 2019 • 9 min read

15022

Want a heads up when a new story comes out?

When we listen to classical music the last thing most of us probably think about is whether or not the piece is in binary form or if a phrase ended on a full or a half cadence. Although such knowledge is not in any way a requirement to appreciate music, it is necessary if you want to fully understand not only what the piece is doing "behind the scenes", but also how the composer is using the conventions to create something truly unique.

Let's think of it this way: when watching a movie you may be shocked to see one of the main characters die right at the beginning right? That will no doubt grab your attention. But you are only shocked by it because you know that the main characters are expected to lead the story until the end. If you had never watched any movie or play, never read or heard any story, you would probably assume that killing the main character was normal and thus not pay much attention to it. What a pity that would have been! Well, in music similar things happen more often than you might think.

So let's quickly learn about two of the most common conventions used in classical music: sentences and periods.

The Sentence

A sentence is a type of musical convention where a theme is divided into 3 phrases. The first two are short, with equal size, and the third one is long, precisely twice as long as one of the previous two. The first and second phrases are directly connected: they can be exactly the same, or the second may repeat the first but with a different harmony. The third phrase should expand on the ideas presented in the first phrase or be a combination of both first and second, in case they were not the same. Let's see some examples to understand what that means.

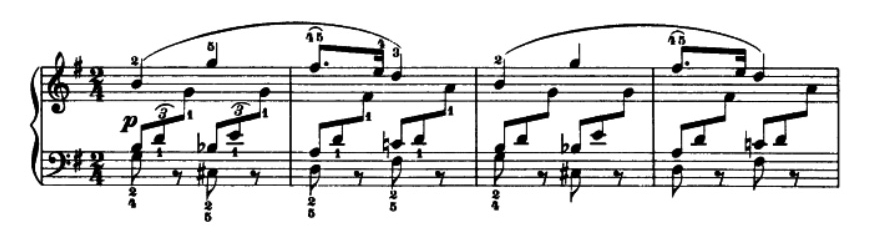

The first example is the first piece from Schumann's cycle Kinderscenen Opus 15. Above you can see the first and second phrases of the sentence. Each phrase is 2 measures long and they are both exactly the same. What should you expect of the next phrase? That should be twice as long, so 4 measures long and expand the melody introduced in these two first phrases. Let's see what happens:

Sure enough, that is exactly what we see! Schumann's makes it very clear that this theme is in sentence form by writing the slur on top of these four measures. If you are a pianist, knowing this will also help you play this piece. Now you know that you should "breathe" between the measures 2 - 3 and again between measures 4 - 5. You should then play measure 5 straight into measure 8 in a straight line, all in one breath.

Sure enough, that is exactly what we see! Schumann's makes it very clear that this theme is in sentence form by writing the slur on top of these four measures. If you are a pianist, knowing this will also help you play this piece. Now you know that you should "breathe" between the measures 2 - 3 and again between measures 4 - 5. You should then play measure 5 straight into measure 8 in a straight line, all in one breath.

Here is how this sounds:

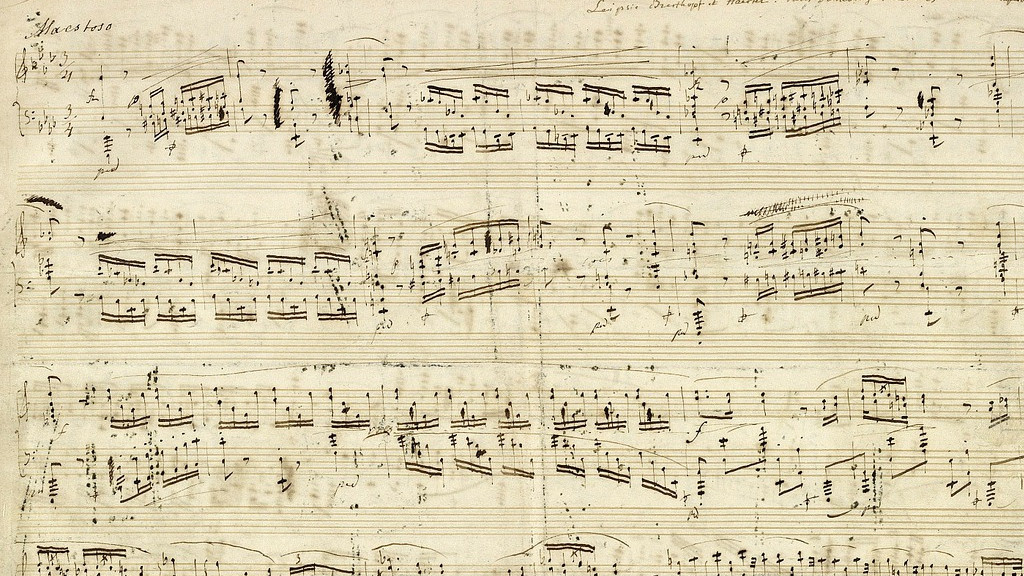

Another great example of a sentence form is the main theme in Beethoven's famous 5th symphony. As you can see below, the first part of this main theme is 4 measures long and, at this point, you probably can already guess how long the second phrase will be! Should be the same, and sure enough, it is. However this time the second phrase is not exactly the same as the first, it is rather a transformed version of the first, presented in the dominant key (a fifth above the original key of C minor, which is G).

Beethoven will then develop the idea of ascending groups of 4 notes in the third phrase. As you might expect, this will be 8 measures long.

Beethoven will then develop the idea of ascending groups of 4 notes in the third phrase. As you might expect, this will be 8 measures long.

We have the main idea being repeated and getting more dramatic as the phrase reaches the end. You will find this form (short - short - long) present in most themes in classical music so, from now on, keep an ear out for it! Here is how this sounds in this example:

We have the main idea being repeated and getting more dramatic as the phrase reaches the end. You will find this form (short - short - long) present in most themes in classical music so, from now on, keep an ear out for it! Here is how this sounds in this example:

The Period

A period is somewhat simpler than a sentence: it is made up of two phrases, both of equal sizes. What is the difference then? They will start in the same way but end in different types of cadences. If you are not sure about what a cadence is, don't worry! The most instinctive way to recognize those two endings is when you hear music that sounds like a question followed by an answer. That is the most typical use of period forms. For this type of theme, we refer to the first phrase as the antecedent and the second phrase as the consequent.

On this first example, Beethoven's Ode To Joy begins with a typical case of a period form.

Notice how this opening of the theme is divided into two phrases, each 4 measures long. Both start in the same way but end differently: the antecedent ends with a question (dominant key of A major) and the consequent ends with an answer (tonic key D major). Here is how this sounds:

Notice how this opening of the theme is divided into two phrases, each 4 measures long. Both start in the same way but end differently: the antecedent ends with a question (dominant key of A major) and the consequent ends with an answer (tonic key D major). Here is how this sounds:

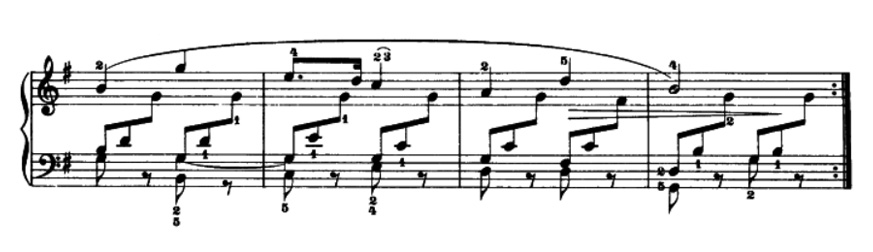

A second example can be found in Mozart's Piano Concerto in F major, K 459. On the image below, you can see the first phrase on bars 1 to 4, the antecedent, ending with a "question" (dominant key of C major) and the second phrase, the consequent, ending with the "answer" (home key of F major).

Here is how this one sounds. Can you pick up on the dialogue-like result of this question - answer structure?

Here is how this one sounds. Can you pick up on the dialogue-like result of this question - answer structure?

•••

In short, sentences and periods are all over the classical repertoire, you will find them in almost every theme in sonatas, symphonies, string quartets, songs, and operas. The structure and form behind movies are mostly the same across all genres and yet we don't usually pay much attention to that. Nor should we! By watching them so much, we learn these rules intuitively and that is why we are shocked or surprised when a movie takes an unusual turn or adds a scene that we didn't expect. Knowing these simple forms and conventions makes classical music so much more entertaining and you will find yourself understanding nuances and details like never before.